In the modern world, we take for granted the idea of the interpreter as the neutral and discreet mediator of other people’s conversation. When world leaders engage, negotiate and tussle with each other, we barely register a thought for the expert linguists whose job it is to seamlessly facilitate them. The perennial price of doing a job too well, it seems, is being taken for granted.

A contribution from Donal, a Dublin-based writer.

The idea of interpreters as agents of political change, as astute strategists or indeed aggressors in their own right, would, in this scenario, border on the absurd. Yet history tells us that not only is this multiplicity of roles possible, but that in at least one instance it has profoundly shaped the world we live in.

In Mexico City’s Plaza de las Tres Culturas, the ruins of the city’s pre-Hispanic past sit humbled by time, side by side with a 16th century church and some bold 1960s buildings. A small plaque notifies visitors that one of the most extraordinary events in history reached its fitful conclusion here. On August 13, 1521, the Aztec empire, then the most powerful political and militaristic force in all of North America, fell to a handful of Spanish conquerors, an event framed by the plaque as ‘neither a triumph nor a defeat, rather the painful birth of the mestizo nation that is Mexico today’.

The Aztecs should really be the stuff of legend rather than verifiable history. Their culture, religion, architecture, artefacts – all the product of a hermetically sealed world in which the wheel had not been invented – seem almost too fantastical to be plausible, an achievement we kindly repay by not bothering to take them too seriously (the unacknowledged debt that science fiction and fantasy literature owes to Aztec and mesoamerican aesthetics generally is a topic for another day). Despite their many achievements – their capital Tenochtitlan was one of the largest and most sophisticated urban centres in the world in the 16th century – to the Western mind, their conquest was so conclusive, their fall so decisive, that their actual existence is largely a sideshow to the project of colonisation that followed their demise. We gloss over what should be impossible to ignore: that our concept of the modern world is largely built on their defeat, and we add insult to injury by making them footnotes to their own history.

In the strange story of their demise, it may seem unlikely that a simple interpreter could play anything more than a passing role. Yet while history gives most credit for the success of the conquest of the Aztecs to the ruthless and pragmatic Spanish adventurer Hernán Cortés, the role of the young native woman who served as his interpreter is perhaps even more fascinating.

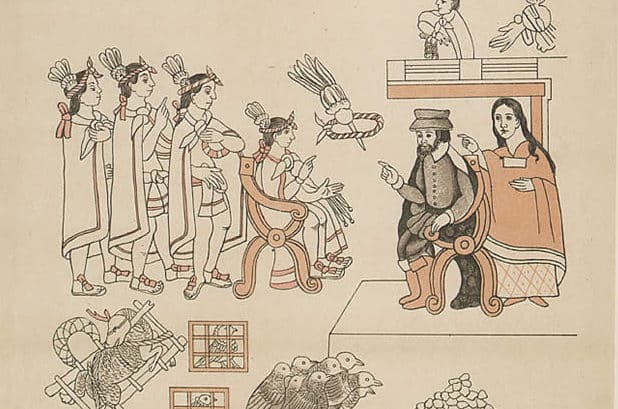

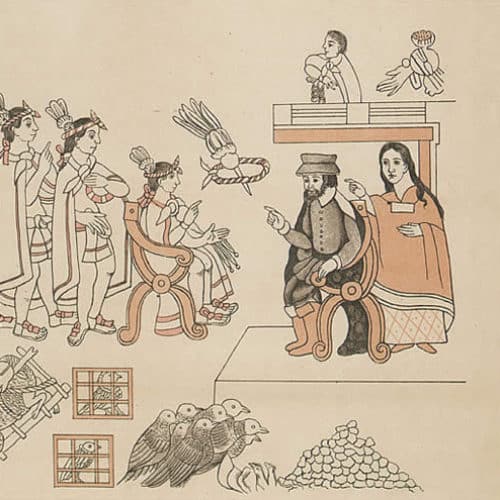

Malinalli, who was christened by the Spanish as Doña Marina, was likely in her late teens when she was given as a gift to the Spanish by a Mayan chief in 1519. Her ability to speak two key native languages Mayan and Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs), gave her immediate value to the new arrivals, and her willingness to learn Spanish, which she mastered in a few months, soon made her indispensable to them. When Montezuma sent his first emissaries to the mysterious pale-skinned strangers who arrived on ‘floating temples’ off the east coast of Mexico, they were first directed to Marina who did nothing to puncture their fear that Cortés was a returned god with vengeance on his mind. When, a few months later, Cortés greeted the emperor on the outskirts of the city of Tenochtitlan, Marina’s skills as an interpreter allowed the Spaniard to pull off one of history’s great confidence tricks. Cortés introduced himself as an ambassador from a great empire across the ocean and with Marina’s help did so with aplomb. It was certainly enough to impress the gullible Montezuma if not some of his more sceptical court. Montezuma has mystified generations of historians with the elaborate and generous greeting with which he welcomed the opportunistic Spaniards. While his welcome should probably have been taken no more seriously than a high-level version of ‘mi casa es su casa’, it was, through Marina, interpreted very literally by Cortés and later offered as evidence of Aztec acceptance of Spanish suzerainty.

While her role as interpreter between Montezuma and Cortés was pivotal, Marina’s understanding of what was a completely alien world to the Spaniards also facilitated some of the deft alliances and defensive moves that gave the Spanish momentum and, ultimately, victory. On the journey to the Aztec capital, the Spanish stopped at the city of Cholula where Marina inveigled details of a planned assault on them from a servant girl. This led the Spanish to initiate a cold-blooded slaughter of the city’s elite, a move that astonished Montezuma when he got wind of it.

While much of what the Spanish later wrote about the conquest was naturally coloured by their own desire for self-justification, the accounts of those who accompanied Cortés confirm that Marina’s role was hugely significant. Early pictorial representations put her right beside him at key moments, and one of the Spaniards to accompany him, Rodríguez de Ocaña, records Cortés as saying that ‘after God, Marina was the main reason for their success’.

Underplaying the role of women is a depressingly well-established norm in mainstream historical narratives, so it can hardly be surprising that Marina’s importance has been downgraded over the centuries. Were it not for the fact that key events would be impossible to understand without her, she would probably have been written out entirely. As is also commonplace for women who are significant in history, information on Marina’s later life is also sparse. It is known that she joined Cortés on further military expeditions and contributed more directly to the birth of Mexico’s new mestizo nation when she herself gave birth to his son Martín (who, years later, would unsuccessfully lead efforts to overturn the conquest). Well rewarded by the Spanish for her help, she is not remembered kindly in Mexico. The nickname Malinche or ‘traitor’ speaks of lingering resentment for a woman who helped a group of outsiders destroy not just the established order but wipe away thousands of years of irreplaceable indigenous civilisation.

Whatever the rights and wrongs of her actions, Marina’s role as interpreter is certainly fascinating to consider. In the modern world, we see it as almost a given that diplomacy is the civilised counterpoint to aggression. Yet, in the conquest of Mexico, it is clear that the language and entente were as much weapons of war as any cannon or spears. In Marina’s hands, they proved to be incredibly potent tools.

Counterfactuals in history are best left to dinner party conversation, but it is reasonable to assume that, had circumstances not played out as they did, a conquest of some kind would ultimately have taken place. A decade later, after all, another ruthless conquistador, Francisco Pizarro, would bring down the huge Inca Empire with an even smaller complement of soldiers, and none of the political niceties practiced by Cortés and Marina. Nevertheless, it remains a fact that a fateful meeting between two powerful and alien civilizations took place at one particular point and that the role of one interpreter was key to facilitating it. It is also a fact that, through the words and actions of this interpreter, the process by which power would ebb inexorably from one of those cultures and flow into the hands of the other began. As a woman who helped steer the course of history, Marina stands as a resolute example of the power of words and language, not just to mediate our understanding of the world but to actively and assertively change it, often with far reaching consequences that can, at the time, only be guessed at.

We LOVE language.